Sunday, January 31, 2021

Alex Papp MD

Suicide is the tenth most common cause of death in the US. It is a terrible loss for the survivors and a great burden to society in general.

Providers of mental health treatments spend a lot of time during their professional education learning about the causes, risks and warning signs of suicidal behavior. We know, for instance, that clinical depression, severe medical illness, having access to means (especially firearms), or family history of suicide predisposes a person to making a suicide attempt. We are told to look for warning signs, such as talking about wanting to die, extremes of guilt and shame, withdrawal form one’s social circle, or giving away possessions. The traditional model of suicide envisions a stepwise buildup of a suicidal impulse, from developing hopelessness to losing connectedness and acquiring the means. A number of questionnaires have been developed during the course of the last few decades to assess the risk scientifically. The “Zero Suicide” movement is gaining traction in mental health. And yet the situation is not improving.

There is a common conception that antidepressants reduce suicidality. That has been conclusively proven only in the over-65 age group. It is not proven in the 25 – 65 age group and we now know that it can cause suicidal ideation in the 15-25 age group.

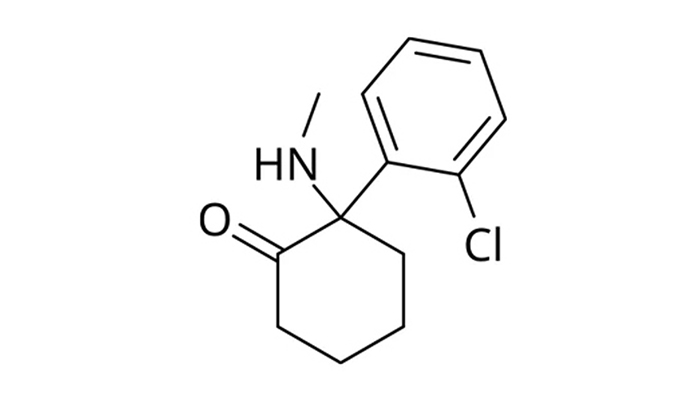

There are only 3 medications that have been proven to have specific antisuicidal effect, none of the three are traditionally considered to be antidepressants. These three medications are clozapine (an antipsychotic), lithium (a mood stabilizer) and ketamine (which, until very recently, was categorized as an anesthetic). There is no known single mechanism that would explain the efficacy of these 3 agents against suicidal ideation and impulses.

All this led to a new and intriguing idea, developed by Dr David Sheehan, that sates that suicidality is a separate disorder, and it can occur as part of depression, but not necessarily. As one of his patients told him: “I am not feeling suicidal because I am depressed, I am depressed because I am feeling suicidal”. Dr Sheehan distinguishes 12 different categories of Suicidal Disorder, among others Impulse Attack, Homicidal, PTSD and Life Event Induced Suicidal Disorders. Dr Sheehan states that our ability to predict individual suicide has not improved in the past 50 years, and the reason for that may be simply that individual suicide is not predictable. A person’s mental journey towards the final act does not follow the gradual ratcheting up of the suicidal desire, as postulated by the stepwise models, but it follows a deterministic chaotic path, wherein a suicidal act may appear unexpectedly. Suicides of seemingly well-functioning people (read this blog entry, for instance). As only societal trends are predictable, individual acts are not, the goal of treatment should be to reduce the strength of suicidal ideation, thereby reducing the statistical risk. You can read more about it on the harmresearch.org website.

Genetics rounds out the picture. Studies found that about 50% of the suicide risk is due to genetic reasons, i.e., it is inherited. The inheritable genetic predisposition combined with the effects of mental illness, with unresolvable difficulties in daily life, with the availability of means, stretches a person’s ability to cope past the limit. It may be never known to the survivors, yet that may be the final push that turns thought into fatal action.